No sooner had Manhattan's municipal water system come into

effect when one of its wells became a crime scene.

No sooner had Manhattan's municipal water system come into

effect when one of its wells became a crime scene.

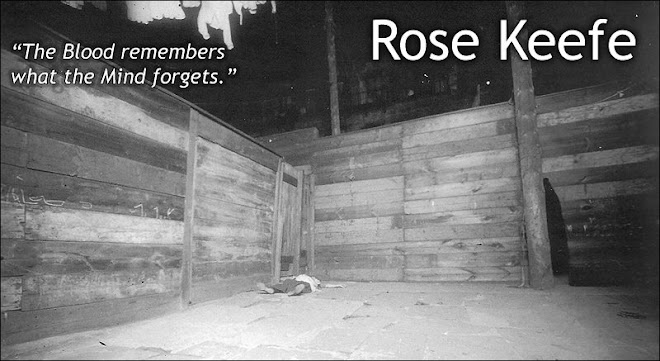

In January 1800, the body of Gulielma ‘Elma' Sands was found floating in the frozen water of a well in Lispenard's Meadow, a marshy terrain near modern day Soho. She had left her Greenwich Street boardinghouse on December 22, 1799 after telling confidants that she intended to be married to carpenter Levi Weeks, who was a fellow boarder. Instead of a bride, Elma became a corpse in a watery grave and the blame was universally cast on Weeks.

Levi’s brother, Ezra, an influential building contractor, hired three prominent lawyers to defend him: former secretary of the treasury and Bank of the United States founder Alexander Hamilton, one-time senator and future Vice President Aaron Burr, and Brockholst Livingston, who went on to become a Justice of the Supreme Court. Although the first two were political adversaries, together with Livingston they formed the young nation’s earliest ‘dream team’. Four years later Burr would kill Hamilton in a duel, but while the trial ran its course, they cooperated so well that the prosecution never stood a chance.

The trial of Levi Weeks was the first American murder trial to be transcribed for posterity, thanks to the new ‘technology’ of shorthand. Eager for details of the ‘Manhattan Well Mystery’, thousands of people attended the proceedings throughout their duration, which was longer than any other American trial to date. Afterwards, future New York Post editor William Coleman published the transcripts in book format.

Duel with the Devil is not merely about a landmark murder mystery: the book reaches out to explore the social customs and political chicanery of post-Revolutionary War New York. A case in point: Aaron Burr’s water company owned the crime scene, had employed Levi Weeks, and rejected a bid by a relative of Elma Sands. According to the author, Burr himself had “financial relationships” with the court recorder and the clerk and past dealings with the mayor and the judge.

Duel with the Devil is another gem by Paul Collins, who also wrote one of my favourite True Crime books: `Murder of the Century'. Collins, who is already celebrated as NPR's "literary detective", once again reveals his genius as a historian and a detective. His theory on the identity of Elma's killer may be as close to the truth as we can get after 214 years.