In April 1895, two young women followed a man they trusted into the Emmanuel Baptist Church in San Francisco’s Mission District and did not emerge alive. The bloody, disfigured corpse of 21-year-old Minnie Williams was found in the library the day before Easter Sunday, and soon afterward searchers discovered the naked body of Blanche Lamont, who had been missing since April 3, in the belfry. Clues and witness statements directed the police to Theo Durrant, a young medical student who also happened to be assistant Sunday School superintendent for the church.

In April 1895, two young women followed a man they trusted into the Emmanuel Baptist Church in San Francisco’s Mission District and did not emerge alive. The bloody, disfigured corpse of 21-year-old Minnie Williams was found in the library the day before Easter Sunday, and soon afterward searchers discovered the naked body of Blanche Lamont, who had been missing since April 3, in the belfry. Clues and witness statements directed the police to Theo Durrant, a young medical student who also happened to be assistant Sunday School superintendent for the church.Durrant’s murder trial was attended by such eminent spectators as Presidential hopeful William Jennings Bryan and Gold Rush millionaire John Mackay. The evidence against him was so overwhelming that the jury brought in a guilty verdict in less than half an hour. While his January 1898 execution brought closure to the families of Minnie Williams and Blanche Lamont, it also left a lot of unanswered questions. Why did he kill two young women whom he’d known well and never born any malice against? And what motivated a man who had been devoted to his parents and sister and active in church affairs to commit murder in the first place? The press hinted that he was a depraved monster disguised as a pious youth, and referred to him as ‘the Demon in the Belfry’. In Sympathy for the Devil, Virginia McConnell questions the justice of these assumptions.

I’ll admit that when I began reading the book, I had doubts about McConnell’s impartiality: in the introduction, she wrote, “His two tragic deeds aside, I would have been proud to call him ‘brother’ or ‘friend’.” But unlike the mindless, adoring women who simpered over Theo Durrant during his courtroom appearances, McConnell has credible reasons for her partiality. Reviewing his family and medical history, she points out that his father was manic-depressive and prone to impulsive actions, and Durrant himself nearly died from meningitis, or ‘brain fever’, a condition that often left survivors with brain damage. She suggests that he may have been in a manic phase when he killed the two women, and the behaviour he exhibited at that time corresponds to the profile: loquaciousness, impulsivity, and unnatural energy levels. When not in the throes of the disorder, Durrant was apparently a mild-mannered, caring individual who placed women on a pedestal.

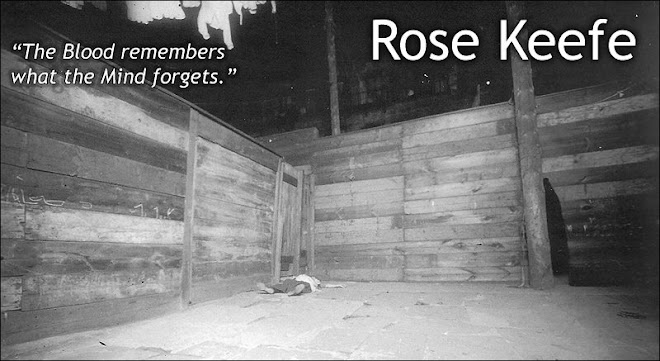

Sympathy for the Devil is a sympathetic, but not sentimental, treatment of the Emmanuel Baptist murders. It includes rare and unsettling photos, such as a vibrant young Blanche Lamont, the belfry landing where her nude body was found, and the blood-spattered walls of the room where Minnie Williams met her death. Any future books about the case have a very high bar to leap over.